Right…just to prove that these practices were common around the Fylde, here’s an extract from the Kirkham parish register dated 1604: “Rushes to strew the church cost this year 9s 6d.” (And possibly a few maidens as well, but they’re not mentioned.)

After a morning spent in quiet Christian devotion, the congregation were given the afternoon off, which was where the fun really began. There was dancing, much quaffing of ale, fighting, May pole dancing, bear baiting, more fighting, drunken revelry, cock fighting, flirting, lots more drinking, eating, no doubt vomiting, arguing, urinating up the side of the ‘rush huts’ and, almost certainly, the traditional late night soliloquy of: “Y’ my bes’ mate, you are…’Av no idea what y’ name is, bu’ y’ my bes’ mate in the ’ole world, ’onest!”

Understandably, perhaps, the more puritanical members of society were not amused.

I don’t usually side with the royal family in political matters, but on this occasion he definitely had a point.

Unfortunately, along came Cromwell, accompanied by one breadbasket, an axe and certain nefarious designs of his own. Off came the king’s head and the wakes celebrations were banished completely.

Several years later, in 1660, after the restoration of the monarchy, the wakes returned, and the chances of this country ever becoming a republic again (we have long memories, especially when it comes to people taking our beer away from us) were utterly quashed.

However, the original zest of the wakes celebrations had been severely diminished and, by the 18th century, they were only pale shades of their former selves.

Here’s what John Lucas had to say about the recently revived festival at St Oswald’s in Warton in the early 18th century: “The feast of dedication…is now annually observed on the Sunday nearest to the first of August, and the vain custom of dancing, excessive drinking, etc., on that day being for many years laid aside, the inhabitants and strangers duly spend the day in attending the service of the church and preparing good cheer within the rules of sobriety in private houses…They cut hard rushes from the marsh, which they make up into long bundles, and then dress them in fine linen, ribbons, silk, flowers, etc.; afterwards the young women take the burdens upon their heads and begin the procession…which is attended with a great multitude of people, with music, drums, ringing bells and all other demonstrations of joy…”

(Sounds a bit like Christian rock music, somehow, doesn’t it? It thinks it’s of a similar ilk to the original, but it’s too watered down and the tambourines are being bashed a bit too excitedly for most people’s tastes.)

Eventually the industrial revolution arrived. The survival of the wakes (despite their tempered appearance) presented the workers with an opportunity not to bother turning up for work, so the mill owners decided to simply close the factories down and overhaul the machinery.

Next up came the railways and certain changes in the law with regard to ‘paid holidays’, allowing the mill workers to spend their holidays in Blackpool. Because the local saints’ days (now extended into weeks, of course, because, after all, where’s the fun in getting completely smashed out of your brains if you’ve got to turn up for work the following morning?) were different for each parish, entire towns would grind to a halt all at once whilst the workers headed off for the coast.

So Blackpool happened, to accommodate the weekly turn over of working class visitors determined to have a good blow out before knuckling down to another fifty-one weeks of abuse and drudgery.

The town grew, and in 1923 its authorities recognised the annual need for grockles debauching themselves so readily that they instigated the first Blackpool carnival. It cost £5,500 to stage and attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors.

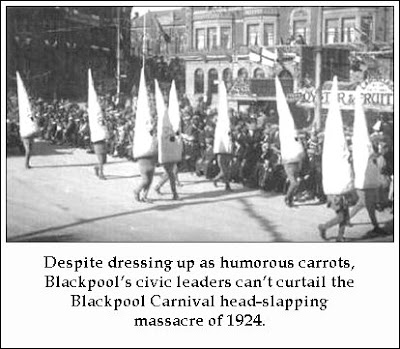

In fact, this almost-similar-but-not-quite-the-same-as-a-rush-bearing-parade proved so popular that the following year another was held. Unfortunately, as is often the case with sequels, this one didn’t meet with the same approval. Get-rich-quick street corner vendors began off-loading inflated bladders on sticks to rowdy customers who’d had slightly more to drink than good-natured buffoonery required. This led to a series of violent head-slapping incidents, resulting in countless beetroot-faced children screaming in agony.

The much-anticipated 1925 Blackpool Carnival never materialised.

The much-anticipated 1925 Blackpool Carnival never materialised.

So that’s basically the story of the Wakes Weeks. Somewhere down the line the original intention seems to have been lost, but the happy-slapping, bladder-wielders no doubt provided some entertainment for any old pagan gods that might have been watching.

5 comments:

They were quick to ring the death knell for a few traditions that immigrated to Oz, too.

Can't have frolicking and jocularity!

the traditional late night soliloquy of: “Y’ my bes’ mate, you are…’Av no idea what y’ name is, bu’ y’ my bes’ mate in the ’ole world, ’onest!”

Some things are the same the world over.

Jayne,

Or lusty maidens on the forest floor...well, not unless you're an aristocrat exercising his droit de signeur.

Andrew,

"Some things are the same the world over."

KFC and MacDonalds to name but two...unfortunately.

I like the engraving of the maypole... does it depict a real place that could be traced by the two buildings engraved within?

And as for old Pagan gods being amused by the mortlas, I can just imagine what they think of us today.

JOHN :0)

John,

I've no idea if the etching depicts an actual place...probably does, but don't ask me where.

As for what the Pagan gods think of us nowadays, as Pratchett was keen to point out, gods rely on belief to exist, so they're probably not thinking much of anything any more.

Post a Comment