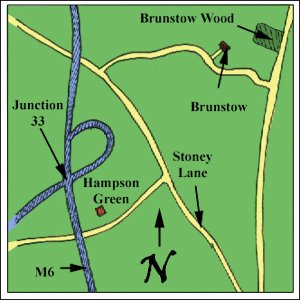

Strictly speaking, Hampson Green (north of Killcrash) doesn’t actually lie within the boundaries of Wyre…or even the Fylde come to that. But, as the metaphorical crow flies, it’s considerably closer to the river than…well…let’s say Cleveleys, which means it’s close enough to warrant a mention here. And why would we want to mention it at all? Well, according to Anthony Hewitson’s ‘Northwards’: “The hamlet of Hampson is about 500 yards from Ellel Grange entrance lodge…” and is so mysterious that: “…not even the date can be recovered of that momentous day when the ‘Hampson Dobby’ fought the ‘Brunsa Hobby’ and both were killed and interred in Dobb’s field.”

Now, at this point the reader is probably muttering, ‘What?’ beneath his/her breath, fumbling for the brew by the side of his/her armchair and rescanning the previous line in order to better understand it. Take our advice and don’t bother. We didn’t understand it either when we first read it, especially seeing that Hewitson added immediately afterwards: “The Dobby was not unamiable, and once in housing the cattle fastened up a hare also. ’Tis said that one good lady presented the creature with a suit of clothes; but on the whole, its life history is obscure.”

‘Obscure’ is probably an understatement. What we actually appear to have here is an ancient folktale, its origins shrouded by the fog of intervening centuries, the original story, no doubt, having been skewed out of all recognisable shape by successive generations. Hewitson wasn’t the only author to relate the tattered remnants of the Dobby’s tale, however. Several other writers also alluded to the poem from which it stemmed which, like its origins, we’ve been unable to locate…most likely because the poem was in fact an oral tradition never set down on paper.

So what exactly was a Dobby? Or even a Hobby? And why does the name ‘Brunsa’ sound so familiar? Why did the two of them fight to the death? Why did the Dobby tie up a hare? And what was so significant about his strange ‘suit of clothes’?

To be honest, we hadn’t a clue, which is why we put on our investigative heads and indulged in a bit of detective work.

The ‘English Dialect Dictionary Volume II’ (published by the Oxford University Press in 1961) informs us that, in Lancashire, a Dobby (also written dobbie) is: “A sprite or apparition with powers of either good or evil.” A bit like a boggart then, really, which might explain why, like the boggart at Hackinsall Hall, the Hampson Dobby helped out with the local farm work. In fact, to quote from Edwin Waugh, one Lancashire abode was: “…said to be haunted by a troubled spirit – a boggart or a ‘dobbie’, as they call it there.”

But there’s more to this than meets the eye. Barrow-in-Furness also had its own Dobby; the Reader’s Digest volume of ‘Folklore, Myths and Legends of Great Britain’ (published in 1973) informing us that a ‘White Dobby’ was once attached to the coastal villages. “It appears like a wandering, weary, emaciated and silent human, and dresses in a dirty white topcoat. Its constant companion is a white hare with glaring, bloodshot eyes.”

A white hare? Now that’s got to be connected with druids and their belief that hares originated in the moon. Albino hares, no doubt, were especially prized because they were white and, as we’ve already discussed somewhere in one of our monthly Wyre Archaeology Newsletters (although we couldn’t say where offhand), white objects appear to have been considered by the druids as particularly important for use in the afterlife. White hares, we even ventured to guess, might have been spiritual guides to lead druidical souls to the moon…all of which puts a different spin on the ‘pigmy urn’ discovered at Bleasdale Circle (might it have contained the remains of an albino hare?) and even the circle itself (was it the burial place of a druid?).

But we’re wandering from the point here. What about the Hampson Dobby’s hare and why did he ‘tie it up’ alongside the cows? Well, now that we’ve learned that a Dobby was actually a Boggart, let’s turn to ‘The Folklore of the Isle of Man’ written by A. W. Moore and published in 1891. Under the heading of ‘The Phynnodderee’ Moore tells us that: ‘The popular idea of the Phynnodderee is that he is a fallen fairy, and that in appearance he’s something between a man and a beast, being covered with black shaggy hair and fiery eyes…”

Or, in other words, a boggart! As Moore continues: “He may be compared with the gruagach, a creature about whom Campbell writes as follows: ‘The gruagach was supposed to be a druid or magician who had fallen from his high estate and had become a strange hairy creature.”

Hold on a moment…so boggarts/gruagachs/phynnodderees are actually druids. And dobbies are boggarts, which makes them druids as well. And that would explain the white hares. So in all probability, if folk memory is correct, the druids were large, hairy people who dressed in white suits?

All of which is fascinating, we’re sure you’d agree, but it still doesn’t explain why the Hampson Dobby tied his hare up in the cowshed.

Back to ‘The Folklore of the Isle of Man’ and those Phynnodderees we’ve just mentioned, about whom Moore writes: “Among the many stories of his having brought sheep home for his farmer friends, there is an often told one of his having, on one occasion, brought home a hare among the rest, and of his having explained that the loghtan beg or ‘little native sheep’ had given him more trouble than all the rest, as it made him run three times round Snaefell before he caught it.”

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? So, the tale of the Hampson Dobby tying up his hare in the cow shed is just another version of the Isle of Man ‘Phynnodderee anecdote’, designed to imply that dobbies/Phynnodderees were a bit on the thick side. In fact, stupidity seems have been part of the qualification for being a dobbie, the ‘English Dialect Dictionary’ telling us that another definition of Dobby is: “A fool, simpleton or stupid fellow.”

But the connections between the Isle of Man and the Wyre don’t end there. Back to the ‘Folklore of the Isle of Man’ and the section concerning local witches and witchdoctors: “These charmers – fer-obbee, ‘men charmers’, and ben-obbee, ‘women charmers’ as they might be either men or women – used certain formulas and practiced various ceremonies for the purpose of curing diseases, or, occasionally, of causing them; and they also made use of their powers to counteract the spells of fairies as well as those of the malevolent sorcerers or witches.”

Phynnodderee…fer-obbee…ben-obbee…dobbies…it’s all starting to connect, isn’t it? Apparently fer-obbee and ben-obbee also used herbs for medicinal purposes, charms and incantations and, despite dabbling in sorcery, they were generally tolerated because their powers were used for good. Does all of this remind you of anyone yet? Do the Culdees, those mysterious inhabitants of keeills who were half-Pagan/half-Christian witchdoctors administering to local villagers spiritual and physical needs, ring any bells?

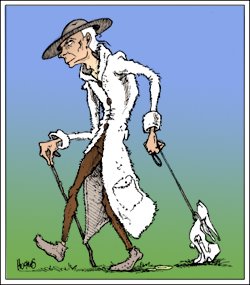

Well…we haven’t finished yet. The ‘Folklore of the Isle of Man’ continues: “One of the best known of these witchdoctors was Teare of Ballawhane, who was described by Train as follows: ‘The seer is a little man, far advanced into the vale of life; in appearance he was healthy and active; he wore a low crowned slouched hat, evidently too large for his head, with a broad brim; his coat, of an old fashioned make, with his vest and breeches, were all of loughtyn wool, which had never undergone any process of dyeing; his shoes, also, were of a colour not to be distinguished from his stockings, which were likewise of loughtyn wool.”

Loughton wool? Wasn’t it Loghtan sheep that the Phynnodderee was rounding up? And wasn’t the Hampson Dobby presented with a special suit of clothes? Loughtyn wool, apparently, when woven also has a speckled, grubby appearance that perfectly matches the White Dobby of Barrow’s ‘dirty white topcoat’.

In fact, when taken as a whole, the evidence suggests that fer-obbee, ben-obbee, Phynnodderee, dobbies and boggarts all stem from the same genus, that being the druids. And how did they manage to survive for so many thousands of years? “To preserve (their) powers intact from generation to generation it was supposed to be necessary to hand them down from a man to a woman, but in the next generation from a woman to a man, and so on.”

So, getting back to our original tale, does any of this explain why the Hampson Dobby and Brunsa Hobby killed each other?

Well, it’s just possible that, at Hampson Green, the local ben-obbee died giving birth to her son the next generation fer-obbee. Then again, perhaps the story simply records a druidical turf war between the culdee/druid/fer-obbee of Hampson Green and the culdee/druid/ben-obbee of nearby Brunstow? It’s difficult to say to what exactly the story refers…but one thing’s almost certain; Dobb’s field (and not having a tithe-map of the area, we don’t know the whereabouts of that particular plot of land) should contain a barrow, the excavation of which might answer all our questions. Unfortunately Hampson Green’s a bit too far to cycle to in the middle of winter so, for the time being at least, that conundrum will have to remain unsolved.

Now, at this point the reader is probably muttering, ‘What?’ beneath his/her breath, fumbling for the brew by the side of his/her armchair and rescanning the previous line in order to better understand it. Take our advice and don’t bother. We didn’t understand it either when we first read it, especially seeing that Hewitson added immediately afterwards: “The Dobby was not unamiable, and once in housing the cattle fastened up a hare also. ’Tis said that one good lady presented the creature with a suit of clothes; but on the whole, its life history is obscure.”

‘Obscure’ is probably an understatement. What we actually appear to have here is an ancient folktale, its origins shrouded by the fog of intervening centuries, the original story, no doubt, having been skewed out of all recognisable shape by successive generations. Hewitson wasn’t the only author to relate the tattered remnants of the Dobby’s tale, however. Several other writers also alluded to the poem from which it stemmed which, like its origins, we’ve been unable to locate…most likely because the poem was in fact an oral tradition never set down on paper.

So what exactly was a Dobby? Or even a Hobby? And why does the name ‘Brunsa’ sound so familiar? Why did the two of them fight to the death? Why did the Dobby tie up a hare? And what was so significant about his strange ‘suit of clothes’?

To be honest, we hadn’t a clue, which is why we put on our investigative heads and indulged in a bit of detective work.

The ‘English Dialect Dictionary Volume II’ (published by the Oxford University Press in 1961) informs us that, in Lancashire, a Dobby (also written dobbie) is: “A sprite or apparition with powers of either good or evil.” A bit like a boggart then, really, which might explain why, like the boggart at Hackinsall Hall, the Hampson Dobby helped out with the local farm work. In fact, to quote from Edwin Waugh, one Lancashire abode was: “…said to be haunted by a troubled spirit – a boggart or a ‘dobbie’, as they call it there.”

But there’s more to this than meets the eye. Barrow-in-Furness also had its own Dobby; the Reader’s Digest volume of ‘Folklore, Myths and Legends of Great Britain’ (published in 1973) informing us that a ‘White Dobby’ was once attached to the coastal villages. “It appears like a wandering, weary, emaciated and silent human, and dresses in a dirty white topcoat. Its constant companion is a white hare with glaring, bloodshot eyes.”

A white hare? Now that’s got to be connected with druids and their belief that hares originated in the moon. Albino hares, no doubt, were especially prized because they were white and, as we’ve already discussed somewhere in one of our monthly Wyre Archaeology Newsletters (although we couldn’t say where offhand), white objects appear to have been considered by the druids as particularly important for use in the afterlife. White hares, we even ventured to guess, might have been spiritual guides to lead druidical souls to the moon…all of which puts a different spin on the ‘pigmy urn’ discovered at Bleasdale Circle (might it have contained the remains of an albino hare?) and even the circle itself (was it the burial place of a druid?).

But we’re wandering from the point here. What about the Hampson Dobby’s hare and why did he ‘tie it up’ alongside the cows? Well, now that we’ve learned that a Dobby was actually a Boggart, let’s turn to ‘The Folklore of the Isle of Man’ written by A. W. Moore and published in 1891. Under the heading of ‘The Phynnodderee’ Moore tells us that: ‘The popular idea of the Phynnodderee is that he is a fallen fairy, and that in appearance he’s something between a man and a beast, being covered with black shaggy hair and fiery eyes…”

Or, in other words, a boggart! As Moore continues: “He may be compared with the gruagach, a creature about whom Campbell writes as follows: ‘The gruagach was supposed to be a druid or magician who had fallen from his high estate and had become a strange hairy creature.”

Hold on a moment…so boggarts/gruagachs/phynnodderees are actually druids. And dobbies are boggarts, which makes them druids as well. And that would explain the white hares. So in all probability, if folk memory is correct, the druids were large, hairy people who dressed in white suits?

All of which is fascinating, we’re sure you’d agree, but it still doesn’t explain why the Hampson Dobby tied his hare up in the cowshed.

Back to ‘The Folklore of the Isle of Man’ and those Phynnodderees we’ve just mentioned, about whom Moore writes: “Among the many stories of his having brought sheep home for his farmer friends, there is an often told one of his having, on one occasion, brought home a hare among the rest, and of his having explained that the loghtan beg or ‘little native sheep’ had given him more trouble than all the rest, as it made him run three times round Snaefell before he caught it.”

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? So, the tale of the Hampson Dobby tying up his hare in the cow shed is just another version of the Isle of Man ‘Phynnodderee anecdote’, designed to imply that dobbies/Phynnodderees were a bit on the thick side. In fact, stupidity seems have been part of the qualification for being a dobbie, the ‘English Dialect Dictionary’ telling us that another definition of Dobby is: “A fool, simpleton or stupid fellow.”

But the connections between the Isle of Man and the Wyre don’t end there. Back to the ‘Folklore of the Isle of Man’ and the section concerning local witches and witchdoctors: “These charmers – fer-obbee, ‘men charmers’, and ben-obbee, ‘women charmers’ as they might be either men or women – used certain formulas and practiced various ceremonies for the purpose of curing diseases, or, occasionally, of causing them; and they also made use of their powers to counteract the spells of fairies as well as those of the malevolent sorcerers or witches.”

Phynnodderee…fer-obbee…ben-obbee…dobbies…it’s all starting to connect, isn’t it? Apparently fer-obbee and ben-obbee also used herbs for medicinal purposes, charms and incantations and, despite dabbling in sorcery, they were generally tolerated because their powers were used for good. Does all of this remind you of anyone yet? Do the Culdees, those mysterious inhabitants of keeills who were half-Pagan/half-Christian witchdoctors administering to local villagers spiritual and physical needs, ring any bells?

Well…we haven’t finished yet. The ‘Folklore of the Isle of Man’ continues: “One of the best known of these witchdoctors was Teare of Ballawhane, who was described by Train as follows: ‘The seer is a little man, far advanced into the vale of life; in appearance he was healthy and active; he wore a low crowned slouched hat, evidently too large for his head, with a broad brim; his coat, of an old fashioned make, with his vest and breeches, were all of loughtyn wool, which had never undergone any process of dyeing; his shoes, also, were of a colour not to be distinguished from his stockings, which were likewise of loughtyn wool.”

Loughton wool? Wasn’t it Loghtan sheep that the Phynnodderee was rounding up? And wasn’t the Hampson Dobby presented with a special suit of clothes? Loughtyn wool, apparently, when woven also has a speckled, grubby appearance that perfectly matches the White Dobby of Barrow’s ‘dirty white topcoat’.

In fact, when taken as a whole, the evidence suggests that fer-obbee, ben-obbee, Phynnodderee, dobbies and boggarts all stem from the same genus, that being the druids. And how did they manage to survive for so many thousands of years? “To preserve (their) powers intact from generation to generation it was supposed to be necessary to hand them down from a man to a woman, but in the next generation from a woman to a man, and so on.”

So, getting back to our original tale, does any of this explain why the Hampson Dobby and Brunsa Hobby killed each other?

Well, it’s just possible that, at Hampson Green, the local ben-obbee died giving birth to her son the next generation fer-obbee. Then again, perhaps the story simply records a druidical turf war between the culdee/druid/fer-obbee of Hampson Green and the culdee/druid/ben-obbee of nearby Brunstow? It’s difficult to say to what exactly the story refers…but one thing’s almost certain; Dobb’s field (and not having a tithe-map of the area, we don’t know the whereabouts of that particular plot of land) should contain a barrow, the excavation of which might answer all our questions. Unfortunately Hampson Green’s a bit too far to cycle to in the middle of winter so, for the time being at least, that conundrum will have to remain unsolved.

5 comments:

John...as requested. (I've even coloured in the original drawings for you.) Give us a couple of weeks and we'll sort out some stuff on the keeill crosses as well.

Excellent story, and very interesting, although it seems a lot more legwork and research might be called for.

I think a lot of these legends do seem to overlap, but don't forget that these are assumptions, and not clear linkages. At the very least, I'm not sure about the links to the druids, but it does seem clear that your area was once frequented by unusual beings that the locals considered non-human, and therefor 'supernatural' attirbutes were assigned to them.

It's quite possible that these dobbies were, like our yeti, offshoots of the human race that survived until modern times. Possibly dim by our standards, or just misunderstood, at least they were able to find odd jobs and be useful in exchange for clothing, food, and the right to survive side by side with their human cousins.

If you want to stretch things a bit, perhaps these creatures gave rise to the legends of brownies, who were small hairy creatures who helped folk out in exchange for a bowl of milk left out for them?

Then again, in small villages where inbreeding occurs, some people of unusual genetics can arise, and not all of them are very bright. These type again would do odd jobs to get by, since back then there weren't many social programs to help those with difficulties. And since there wasn't all that much to go around, perhaps 2 of these beings had to fight it out for territorial rights?

Either way, I look forward to hearing more of these legends, and I encourage you to gather this information before it is completely lost to time.

Great stuff! JOHN :0)

John...pixies (originally Pictsies) are the Scottish equivalent. It's intetresting to read the old folk tales...the original ones that is as opposed to the Victorian fairy tales. Faerie folk were originally human sized, attacked adults, abducted children and lived inside the hills. Bronze Age arrow heads discovered in barrows were often refered to as 'Elf Shot' or 'Faerie Shot' so there's a definite connection to the distant past. One of the problems we're dealing with in interpreting these ancient stories is that, when the Romans invaded, they effectively broke the back of the druidical stranglehold over Britain and destroyed any written literature and history. Believe it or not, despite certain historians claiming different, the Druids did keep written records...written in a form of Runic Ogham most likely...some of which survived until the Anglo-Saxons once again imposed their religious fundamentalism on the land, at which point, according to documents we've read, they were shipped out of the country into mainland Europe and, effectively, lost. I'd love to get my hands on some of them.

The druidic/culdee/keeill connection is considerably more complicated than what we've written here but the evidences do strongly suggest connections.

At some point I'll have to post the Legend of Parlick's Dun Cow for you...considering its proximity to Bleasdale Circle that one's certainly an enigma.

Hi Brian,

Much of this is new to me, especially as pertains to your local legends. Undoubtedly, there are connections that a newbie like myslef doesn't see yet, and let's be honest, this article alone covers a lot of ground.

Let's agree, though, that when it comes to ancient legends (using the term ancient loosely), one must be careful in imposing modern assumptions, paradigms, and language upon them. As you say, the Victorians weren't averse to editing content for cuteness, and Geezers in pubs have been known ( sit down for this) to 'embellish' tales, to not only make them more outlandish, but to earn themselves another round of Himself's finest.

These tales are great fun on their own, but I admire you guys for looking deeper. Sometimes the truth can be just as interesting as the fiction it later becomes.

I look forward to the Legend of Parlick's Dun Cow. I also look forward to getting my hands on the rest of your books. I certainly enjoyed "The Ancient History of the Wyre."

Cheers, JOHN :0)

John

I totally agree. It's incredibly difficult to strip away the Victorian censorship, the mediaeval Anglican/Christian bias and the 'Chinese Whispers' effect of these ancient legends. We're just having a stab in the dark, that's all, coupling the legends with what limited knowledge we already have of the local ancient archaeology. It's difficult to say how accurate or inaccurate our interpretations might be at this point...but it's a start. Very few people around these parts even realise that we have an ancient history so, if we're ever to get the ball rolling, somebody's got to take a shot in the dark I reckon. We're laying our reputations (such as they are) on the line with this stuff...we can only hope that historians in the future who are better equipped than we are judge us kindly.

Post a Comment