(The following article and the first article ever posted on this board are in the wrong order. That's what happens with recycling I'm afraid. It does, however, mean that once you've read this particular offering, the original posting might make more sense. We say 'might', of course, with a certain amount of optimism...)

The enigmatic if not brutal sounding ‘Killcrash’ occurs at least twice in Wyre place names, the first at Nateby (Killcrash Lane) and the second as a small district just east of Forton Hall. The name Kilntrees (written as Kill Trees on ancient maps) also falls directly between these two and Killcrash crops up once again at Barton in the Fylde.

All which leads us to ask the following questions: “What exactly does the word ‘Killcrash’ mean? Is it related to some ancient battlefield? (Resurrections of Brunanburh spring to mind.) Or is it derived from some other long forgotten place or event?”

Obviously we couldn’t let such questions go unanswered so, following a quick study of our heavily pencilled archaeological maps, we soon discovered that at Nateby, Killcrash Lane is bisected by the Garstang to Hambleton Romano/Brythonic road, both Kilntrees and Killcrash near Forton fall on the Walton-le-Dale to Lancaster Roman road and the Killcrash at Barton stands on the Ribchester to Lancaster Roman highway.

So, Killcrash must surely have had something to do with the Romans then?

Well…probably not. We’re forgetting here that the Norse were notoriously lethargic at road construction, their villages and other wayside entertainments falling alongside earlier Roman roads because these thoroughfares were already in place.

By way of confirmation, at both Forton and Kilntrees suspected Norse crosses have been discovered, the Kilntrees cross now standing to attention behind a hedgerow at Cabus as shown in the photograph below.

Before we get any complaints about its origins, Headlie Lawrenson informed us by letter that: “We discovered the Cabus Cross Roads cross in the late 50’s when we were doing some excavations on the Walton-le-Dale – Lancaster Roman road. It was…doing duty as a gate post on Kiln Trees Farm.”

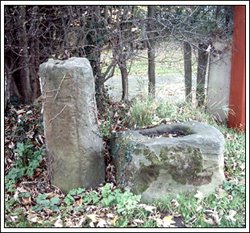

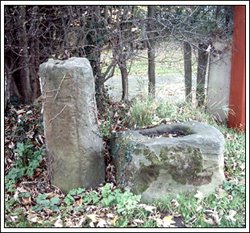

The Forton Hall cross was broken twice whilst serving time as a gatepost. The single remaining section can now be found in Alvin Cook’s garden at Cockerham whilst the rest, unfortunately, lies buried beneath a field near Forton Hall. The base, however, still remains next to the Roman milestone on the corner of Stoney Lane, as shown in the photograph below.

So…all things considered then, surely the name ‘Killcrash’ must be of Norse origin…mustn’t it?

Not completely convinced we went hunting for more answers and unearthed a few fascinating facts along the way.

For example in ‘Manks Antiquities’ written by P. M. C. Kermode and W. A. Herdman, we’re informed that: “The Manx word keeill derived from the Latin Cella, or, as has been supposed, from an older Celtic word meaning a grave, is the same as the Irish and Gaelic Cill or Kil, met with as a compound in so very many place names.”

And the Survey of English Place-names by A. Mawer tells us that: “The Irish cruach, the Welsh crug, and the Cornish, Breton cruc, (all mean) ‘hill or barrow’”

With these facts in place, it isn’t terribly difficult to see how the compound word ‘Keeill-cruach’ became corrupted through our local dialect to the simpler term ‘Killcrash’. So, what we appear to have here are at least three ancient burial grounds with the possibility of their accompanying Norse/Manx/Romano-Brythonic chapels.

Didn’t we mention the chapels?

Oh…hold on, here’s what ‘Keeills of the Isle of Man’ has to say on the subject: “A keeill is an early Christian chapel dating from before the introduction of the parochial system in the twelfth century. In the sixth century there emerged a class of clergy, independent of the monasteries, who lived a solitary and austere life. These recluses known as Culdee’s (from Cele De or servant of God) from the eighth century would build their own cells or oratories (keeills) and act as spiritual fathers to local families.”

And from ‘Manks Antiquities’: “We know that at the introduction of Christianity into other Celtic lands, when a grant of land was obtained from the chieftain – if indeed he did not present them with a fort – it was customary for the missionary to erect a ‘Lis’ or ‘Caisel’, within which to place his church as well as the dwellings of those who became Christians, and that this custom was long continued.”

So a Culdee lived in a keeill and was a sort of cross between a hermit and a priest, administering spiritual advice to local inhabitants and, occasionally, conducting the odd religious service to boot. Pretty much the sort of relationship that Merlin had with Arthur really…but let’s not go there.

To return to ‘Manks Antiquities’: “If, as is not unlikely, the very earliest churches in the Isle of Man were as elsewhere built of sods or of wattle and mud, there are now no remains of such; but, in one or two instances burial places have been found with lintel-graves of the Christian period yet with neither trace nor tradition of a building, and this may possibly be due to the fact that such buildings were of mud and not replaced by stone.”

Ancient burial sites and the ghosts of incredibly early Christian churches at Forton and Nateby? Surely not!

Let’s take another look at those mysterious crosses, shall we? The Cabus shaft (as can be seen in the photograph above) is inscribed with a roughly hewn cross. The same was originally true of the cross shaft at Forton, the photographs supplied by Alvin Cook being proof of this.

Until recently we believed these crude carvings to be the work of mediaeval monks, recycling the cross shafts for monastic boundary markers. Now, however, armed with new information, we’ve had a change of heart. According again to ‘Manks Antiquities’ these rough markings are indicative of early keeills, the book supplying us with a range of drawings that bear striking similarities to our own ‘boundary markers’.

Interestingly, the suffix ‘Trees’ in Kill Trees generally denotes a boundary, probably the border between the Forton and Nateby keeills. So that’s the Cabus cross sussed out then.

But what about the Forton cross? Well, right at this moment in time we’ve no idea what it originally represented. Perhaps it marks the burial site of the Culdee who lived in the keeill. Then again it might mark the site of the keeill itself. Whatever the case, working on the assumption that the Forton and Nateby keeills existed, what sort of remains might we be looking for?

Back to ‘Manks Antiquities’ again: “The plan is invariably rectangular. There is no apse or rounded end, but the east gable like the west is at right angles to the side walls. Even more remarkable is the fact that there was no architectural division between the nave and the chancel.”

And ‘Keeills of the Isle of Man’: “Usually the keeill was built upon a natural or artificial elevation in the terrain and had attached to it a burial ground, surrounded by a mound which in height could reach five to six feet. The whole plan of the keeill recalls, on a small scale, a rath or a liss, upon which it was certainly modelled.”

For anybody not familiar with those terms, a ‘rath’ or a ‘liss’ was a small hill-fort.

One final word from ‘Manks Antiquities’: “A remarkable thing is that many keeills prove to have been erected on older heathen burial sites which, so far, appear to all have been of Bronze Age – not only worked flints and charcoal and burnt bones being found, but fragments of pottery of that period. In every case white shore pebbles were met with, sometimes in great numbers, and some previously undisturbed graves showed that sometimes, at all events, these had been used to cover them and soil was then heaped on top.”

Now, at Nateby (recorded ‘Natebi’ in the Doomsday book suggesting that the village itself was established by the Norse) Killcrash Lane heads directly towards the possible Bronze Age barrow behind the gymnasium that we’ve reported on before.

True to the description of the keeills previously mentioned this, as yet unexcavated, earthwork is surrounded by an embankment. In its immediate vicinity, of course, stand plenty more recognised Bronze Age earthworks, so is this one of our missing keeills? Or could the location of the Nateby keeill fit one of the many other unidentified earthworks that populate the area?

As for the ‘Keeill-cruach’ east of Forton, we haven’t had the opportunity to check out the surrounding landscape for possible clues yet. (It’s a heck of a long way to cycle on pushbikes…especially in the sort of gale force winds we’ve been experiencing recently.) So, for the time being at least, its exact whereabouts will have to remain a mystery. Naturally, we’ll keep you posted on any developments.

All which leads us to ask the following questions: “What exactly does the word ‘Killcrash’ mean? Is it related to some ancient battlefield? (Resurrections of Brunanburh spring to mind.) Or is it derived from some other long forgotten place or event?”

Obviously we couldn’t let such questions go unanswered so, following a quick study of our heavily pencilled archaeological maps, we soon discovered that at Nateby, Killcrash Lane is bisected by the Garstang to Hambleton Romano/Brythonic road, both Kilntrees and Killcrash near Forton fall on the Walton-le-Dale to Lancaster Roman road and the Killcrash at Barton stands on the Ribchester to Lancaster Roman highway.

So, Killcrash must surely have had something to do with the Romans then?

Well…probably not. We’re forgetting here that the Norse were notoriously lethargic at road construction, their villages and other wayside entertainments falling alongside earlier Roman roads because these thoroughfares were already in place.

By way of confirmation, at both Forton and Kilntrees suspected Norse crosses have been discovered, the Kilntrees cross now standing to attention behind a hedgerow at Cabus as shown in the photograph below.

Before we get any complaints about its origins, Headlie Lawrenson informed us by letter that: “We discovered the Cabus Cross Roads cross in the late 50’s when we were doing some excavations on the Walton-le-Dale – Lancaster Roman road. It was…doing duty as a gate post on Kiln Trees Farm.”

The Forton Hall cross was broken twice whilst serving time as a gatepost. The single remaining section can now be found in Alvin Cook’s garden at Cockerham whilst the rest, unfortunately, lies buried beneath a field near Forton Hall. The base, however, still remains next to the Roman milestone on the corner of Stoney Lane, as shown in the photograph below.

So…all things considered then, surely the name ‘Killcrash’ must be of Norse origin…mustn’t it?

Not completely convinced we went hunting for more answers and unearthed a few fascinating facts along the way.

For example in ‘Manks Antiquities’ written by P. M. C. Kermode and W. A. Herdman, we’re informed that: “The Manx word keeill derived from the Latin Cella, or, as has been supposed, from an older Celtic word meaning a grave, is the same as the Irish and Gaelic Cill or Kil, met with as a compound in so very many place names.”

And the Survey of English Place-names by A. Mawer tells us that: “The Irish cruach, the Welsh crug, and the Cornish, Breton cruc, (all mean) ‘hill or barrow’”

With these facts in place, it isn’t terribly difficult to see how the compound word ‘Keeill-cruach’ became corrupted through our local dialect to the simpler term ‘Killcrash’. So, what we appear to have here are at least three ancient burial grounds with the possibility of their accompanying Norse/Manx/Romano-Brythonic chapels.

Didn’t we mention the chapels?

Oh…hold on, here’s what ‘Keeills of the Isle of Man’ has to say on the subject: “A keeill is an early Christian chapel dating from before the introduction of the parochial system in the twelfth century. In the sixth century there emerged a class of clergy, independent of the monasteries, who lived a solitary and austere life. These recluses known as Culdee’s (from Cele De or servant of God) from the eighth century would build their own cells or oratories (keeills) and act as spiritual fathers to local families.”

And from ‘Manks Antiquities’: “We know that at the introduction of Christianity into other Celtic lands, when a grant of land was obtained from the chieftain – if indeed he did not present them with a fort – it was customary for the missionary to erect a ‘Lis’ or ‘Caisel’, within which to place his church as well as the dwellings of those who became Christians, and that this custom was long continued.”

So a Culdee lived in a keeill and was a sort of cross between a hermit and a priest, administering spiritual advice to local inhabitants and, occasionally, conducting the odd religious service to boot. Pretty much the sort of relationship that Merlin had with Arthur really…but let’s not go there.

To return to ‘Manks Antiquities’: “If, as is not unlikely, the very earliest churches in the Isle of Man were as elsewhere built of sods or of wattle and mud, there are now no remains of such; but, in one or two instances burial places have been found with lintel-graves of the Christian period yet with neither trace nor tradition of a building, and this may possibly be due to the fact that such buildings were of mud and not replaced by stone.”

Ancient burial sites and the ghosts of incredibly early Christian churches at Forton and Nateby? Surely not!

Let’s take another look at those mysterious crosses, shall we? The Cabus shaft (as can be seen in the photograph above) is inscribed with a roughly hewn cross. The same was originally true of the cross shaft at Forton, the photographs supplied by Alvin Cook being proof of this.

Until recently we believed these crude carvings to be the work of mediaeval monks, recycling the cross shafts for monastic boundary markers. Now, however, armed with new information, we’ve had a change of heart. According again to ‘Manks Antiquities’ these rough markings are indicative of early keeills, the book supplying us with a range of drawings that bear striking similarities to our own ‘boundary markers’.

Interestingly, the suffix ‘Trees’ in Kill Trees generally denotes a boundary, probably the border between the Forton and Nateby keeills. So that’s the Cabus cross sussed out then.

But what about the Forton cross? Well, right at this moment in time we’ve no idea what it originally represented. Perhaps it marks the burial site of the Culdee who lived in the keeill. Then again it might mark the site of the keeill itself. Whatever the case, working on the assumption that the Forton and Nateby keeills existed, what sort of remains might we be looking for?

Back to ‘Manks Antiquities’ again: “The plan is invariably rectangular. There is no apse or rounded end, but the east gable like the west is at right angles to the side walls. Even more remarkable is the fact that there was no architectural division between the nave and the chancel.”

And ‘Keeills of the Isle of Man’: “Usually the keeill was built upon a natural or artificial elevation in the terrain and had attached to it a burial ground, surrounded by a mound which in height could reach five to six feet. The whole plan of the keeill recalls, on a small scale, a rath or a liss, upon which it was certainly modelled.”

For anybody not familiar with those terms, a ‘rath’ or a ‘liss’ was a small hill-fort.

One final word from ‘Manks Antiquities’: “A remarkable thing is that many keeills prove to have been erected on older heathen burial sites which, so far, appear to all have been of Bronze Age – not only worked flints and charcoal and burnt bones being found, but fragments of pottery of that period. In every case white shore pebbles were met with, sometimes in great numbers, and some previously undisturbed graves showed that sometimes, at all events, these had been used to cover them and soil was then heaped on top.”

Now, at Nateby (recorded ‘Natebi’ in the Doomsday book suggesting that the village itself was established by the Norse) Killcrash Lane heads directly towards the possible Bronze Age barrow behind the gymnasium that we’ve reported on before.

True to the description of the keeills previously mentioned this, as yet unexcavated, earthwork is surrounded by an embankment. In its immediate vicinity, of course, stand plenty more recognised Bronze Age earthworks, so is this one of our missing keeills? Or could the location of the Nateby keeill fit one of the many other unidentified earthworks that populate the area?

As for the ‘Keeill-cruach’ east of Forton, we haven’t had the opportunity to check out the surrounding landscape for possible clues yet. (It’s a heck of a long way to cycle on pushbikes…especially in the sort of gale force winds we’ve been experiencing recently.) So, for the time being at least, its exact whereabouts will have to remain a mystery. Naturally, we’ll keep you posted on any developments.

2 comments:

Another great post, especially since you included a lot of definitions with this one, which I found to be very helpful.

Are there any plans for professional excavations of any of these burial mounds? And could a very vareful excavation reveal proof of a keeill? Surely, even if made of mud, the ruins would reveal some proof of your suspicions? If somebody lived there, wouldn't there be something left behind?

It would be great to confirm your findings, and perhaps that buried cross could be excavated and restores to it's rightful place as well?

Thanks again for an interesting posting, JOHN :0)

John,

We were hoping to excavate 'Kelbreck Field' at Stanah to see if we could find the keeill there, but unfortunately there's absolutely no sign of any fosse or other structure on the surface. After one and a half thousand years of ploughing and planting this isn't particularly surprising. But, in order to excavate, we'd have to narrow down our area to within a few yards at least first...and, in Stanah's case, that's just not possible. There are other places to investigate yet, though, that might not have been so intensely farmed over the centuries. Here's keeping our fingers crossed.

Post a Comment