Perhaps it’s their intransigent architecture and immovability in the landscape that generates a blind spot for some historians when it comes to local churches. It’s easy to forget that buildings such as St. Helen’s have actually been standing for over a thousand years, their origins now lost to an age before the Tower of London was even a twinkle in William of Normandy’s tyrannical eye. In fact, it’s just possible that several of our long-established churches began life as keeills, those shadowy structures combining both Pagan and Christian beliefs, controlled by mystical druid-like wise men and standing on the ancestral burial grounds of the ancients. What makes us think this? Well, we’re glad you asked.

St. Helen’s in Churchtown was originally known as Kirklund; a combination of the Norse word ‘Kirk’ meaning ‘Church’ (although occasionally it could refer to a ‘stronghold’) and the Celtic word ‘Lund’ referring to a ‘Sacred Grove’. Groves, of course, were of religious significance to the Celts, their veneration of oaks resulting in such national monuments as Wood Henge and Bleasdale Circle. Kirks, as we’ve probably mentioned before, were the Norse descendants of Keeills. Not that there’s much in the way of the original building left at St. Helen’s now, most keeills having been constructed of wood or loose stones and measuring only a few feet from top to toe.

Look closely, however, and you might just uncover evidence of St. Helen’s pre-Norman past.

St. Helen’s in Churchtown was originally known as Kirklund; a combination of the Norse word ‘Kirk’ meaning ‘Church’ (although occasionally it could refer to a ‘stronghold’) and the Celtic word ‘Lund’ referring to a ‘Sacred Grove’. Groves, of course, were of religious significance to the Celts, their veneration of oaks resulting in such national monuments as Wood Henge and Bleasdale Circle. Kirks, as we’ve probably mentioned before, were the Norse descendants of Keeills. Not that there’s much in the way of the original building left at St. Helen’s now, most keeills having been constructed of wood or loose stones and measuring only a few feet from top to toe.

Look closely, however, and you might just uncover evidence of St. Helen’s pre-Norman past.

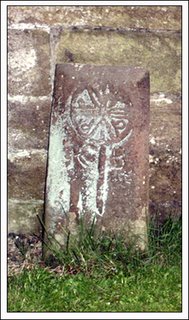

The carved slab above (it would be wrong to call it a gravestone as it probably isn’t), which can be found leaning against the vestry, is most likely a form of Keeill cross. It doesn’t resemble the familiar shafts like those at Cabus and Forton it must be said, both forerunners to the more elaborately carved Viking Crosses, but it does bear a Chi-Rho motif similar to one discovered at Maughold (a known keeill) on the Isle of Man which dates to the eighth century. The ‘P’ and ‘X’ symbols interspersed with the decoration commonly occur in Romano/Christian mosaics and stem from the first two letters of Christ’s name in Greek.

Leading to the church from almost every direction are the bases of wayside crosses, such as the one in the photograph below that stands on the corner of Goose Lane.

Leading to the church from almost every direction are the bases of wayside crosses, such as the one in the photograph below that stands on the corner of Goose Lane.

These are commonly believed to have been points of sanctuary during the mediaeval period for weary coffin bearers unable to rest their cargo on unhallowed ground. A quick study, however, reveals that they’re anything other than Saxon and more akin to keeill cross bases.

Then there’s the fact that St. Helen’s is built on an oval-shaped mound, typical of prehistoric burial sites and considered by many Wyre antiquarians to be just that. All of which brings us back to our archaeological research and begs the question: “As Kirklund appears to have been an isolated Norse/Celtic community was there a Romano/British road linking it to Nateby or Catterall, most keeills in this district having been built within a few hundred yards of Roman roads?”

Then there’s the fact that St. Helen’s is built on an oval-shaped mound, typical of prehistoric burial sites and considered by many Wyre antiquarians to be just that. All of which brings us back to our archaeological research and begs the question: “As Kirklund appears to have been an isolated Norse/Celtic community was there a Romano/British road linking it to Nateby or Catterall, most keeills in this district having been built within a few hundred yards of Roman roads?”

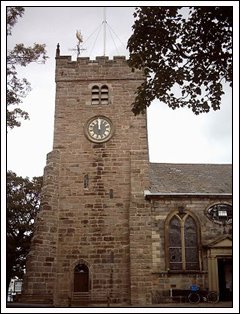

St. Chad’s in Poulton, shown in the photograph above, is known to stand in the vicinity of the Danes’ Pad; not actually adjacent to it, as some people think, but several hundred yards to the west on what appears to be another barrow. As though in confirmation of this, in his book ‘The History of St Chad’s Church’ J. Scott Ashton mentions that: “At one time the churchyard was partly surrounded by a ditch.”

That the burial ground might have been of Romano/Celtic origin (not only were the local Celts content to mix their pagan beliefs with Christianity, it seems, but also with any other friendly/occupying culture as evidenced by the Mars Nodens figurines discovered at Cockersands in the eighteenth century) is backed-up by the discovery of two copper coins dating from the reign of Emperor Hadrian found near the church and a large medal of Germanicus unearthed in a garden at the rear of Poulton market.

If you’re still not convinced about St. Chad’s origins, then it might be worth considering a legal document dating from 1357 concerning a dispute by John, son of Adam le Wayte, over an oxgang of land which refers to Kirk Poulton.

Another probable keeill/kirk conversion is St. Mary’s in Hambleton. Although the church itself was rebuilt in 1973 the churchyard is surrounded by a ditch, suggesting that the original building stood, once again, on a pagan site. As Peter Myerscough of the Evening Gazette wrote: “Little is known of the church’s past. An Episcopal chapel was consecrated in 1567, but there was probably a chapel of ease to Kirkham there at a much earlier date.”

Then, of course, there’s Newers Wood in Pilling, built on an oval burial mound and showing all the usual signs of having evolved from a keeill.

So why did some of the keeills survive and flourish, becoming the churches we’d recognise today such as St. Chad’s and St. Helen’s, whilst others, like Newers Wood, fell from grace, so to speak, most ending up with nothing more to remember them by other than fieldnames? Well, the answer to that is probably two-fold. Firstly, centres of population for reasons best left to antiquity tended to drift, in the case of Newers Wood a chapel closer to the centre of Pilling being called for in 1717. Other keeills, however, might simply have failed to adapt, firstly to the Romanised version of the church which forbade the worshipping of idols and adherence to pagan ideology, and latterly to Anglicanism.

Dig beneath the grounds of any of our ancient churches and you might just discover, interspersed with those Christian corpses waiting in line for Judgement Day, the unaligned bodies and/or cremated remains of our earlier ancestors. As for exactly how many, as yet, undiscovered keeills and their associative barrows still remain dotted around the Wyre (there are over 400 such sites in the Isle of Man alone) only time and excavations will tell.

That the burial ground might have been of Romano/Celtic origin (not only were the local Celts content to mix their pagan beliefs with Christianity, it seems, but also with any other friendly/occupying culture as evidenced by the Mars Nodens figurines discovered at Cockersands in the eighteenth century) is backed-up by the discovery of two copper coins dating from the reign of Emperor Hadrian found near the church and a large medal of Germanicus unearthed in a garden at the rear of Poulton market.

If you’re still not convinced about St. Chad’s origins, then it might be worth considering a legal document dating from 1357 concerning a dispute by John, son of Adam le Wayte, over an oxgang of land which refers to Kirk Poulton.

Another probable keeill/kirk conversion is St. Mary’s in Hambleton. Although the church itself was rebuilt in 1973 the churchyard is surrounded by a ditch, suggesting that the original building stood, once again, on a pagan site. As Peter Myerscough of the Evening Gazette wrote: “Little is known of the church’s past. An Episcopal chapel was consecrated in 1567, but there was probably a chapel of ease to Kirkham there at a much earlier date.”

Then, of course, there’s Newers Wood in Pilling, built on an oval burial mound and showing all the usual signs of having evolved from a keeill.

So why did some of the keeills survive and flourish, becoming the churches we’d recognise today such as St. Chad’s and St. Helen’s, whilst others, like Newers Wood, fell from grace, so to speak, most ending up with nothing more to remember them by other than fieldnames? Well, the answer to that is probably two-fold. Firstly, centres of population for reasons best left to antiquity tended to drift, in the case of Newers Wood a chapel closer to the centre of Pilling being called for in 1717. Other keeills, however, might simply have failed to adapt, firstly to the Romanised version of the church which forbade the worshipping of idols and adherence to pagan ideology, and latterly to Anglicanism.

Dig beneath the grounds of any of our ancient churches and you might just discover, interspersed with those Christian corpses waiting in line for Judgement Day, the unaligned bodies and/or cremated remains of our earlier ancestors. As for exactly how many, as yet, undiscovered keeills and their associative barrows still remain dotted around the Wyre (there are over 400 such sites in the Isle of Man alone) only time and excavations will tell.

7 comments:

An excellent blog, full of wonderful observations! I agree with you on all counts, but have just one question.

What's a Keeill?

Cheers, JOHN :0)

PS Look forward to more of the fascinating history of the Wyre, a land of charming mystery and guile. A land that I can only dream about, unless of course The Fylde Country Life Heritage Centre

will be holding any contests soon, where the grand prize is an all expenses paid trip for four to Lancashire?

John...as excellent as the Fylde Country Life Museum is (and, trust me, it is...you'd be surprised at how much there is in it), it can't even afford to pay for my bus fare from Fleetwood when I want to get down there and lend a hand. As for what a keeill is...stayed tuned...there will be more.

A definition of a keeill would be great for those of us who appreciate archeology, but aren't as well versed in it's terminology.

I did find it fascinating that some churches were built on mounds. The UK is full of examples of churches built on ancient 'spiritual sites', such as St. Pauls in London, and even using materials from former sites, such as the Abbey in Bath, but this is the first that I have heard of building on mounds.

Is there any evidence that these are indeed stone age burial mounds? The surrounding ditch does give the mounds the appearance of stone age construction, but as we all know, appearances can be deceiving. Perhaps this ditch and mound design was used simply to prevent wet floors during the rainy season?

Surely somebody somewhere has thought of doing exploratory excavation on one of these mounds, although I can see that the church might frown on this in practice.

Looking forward to more! JOHN :0)

John...

The easiest way to define a keeill is as a small church, part Pagan/ part Christian, dating from around the fifth to eighth centuries. They often consisted of nothing more than an upturned boat (usually the one in which the missionary arrived) and the spiritual leader (known as a Culdee) would service several local communities.

Culdees were often granted rights to erect their keeills by local chieftans on ancestral burial grounds (presumably because of the holy significance).

The chapel at Newers Wood in Pilling, as far as we can tell, was originally a keeill although it was much later (around the 12th century) redeveloped by Cockersands Abbey. The original building stood, as you'd expect, on a circular burial ground and several excavations there in the last half a century have indeed turned up pagan artefacts alongside Christian burial practices.

Hope that helps.

Fiona...you don't know what a keeill is? Does anybody actually read the Wyre Archaeology newsletters? I dunno...Michelle and I spend all that time putting these things together...we're usually drunk when we do it but...still...

Enjoy university...the first two weeks will be awful, no doubt, but after that everything changes (and I speak from experience, so stick with it). This'll be the best time of your life...so try to stay sober for some it so you'll remember.

See you at Christmas...if you haven't forgotten us old amateur fogies by then of course,

Brian.

Hmmm...two comments for the price of one...time I upgraded to broadband I reckon.

Post a Comment